When you are preparing your weekly trash collection, sorting different waste in the various recycling categories – have you considered what happens in the next stage of the process, after it has been collected?

According to Eurostat, 5.2 tonnes of waste are generated per EU inhabitant each year. 38.5% of that waste goes to landfill and 37.9% gets recycled. Numbers that can certainly be improved, if the EU can advance the concept of the circular economy within the bloc. The basic concept of a circular economy is simple: waste from one source can become a valuable input for another use. The circular economy action plan is a cornerstone of the European Union’s sustainability strategies: it aims to ensure that products and materials are recycled or reused rather than simply discarded after initial use.

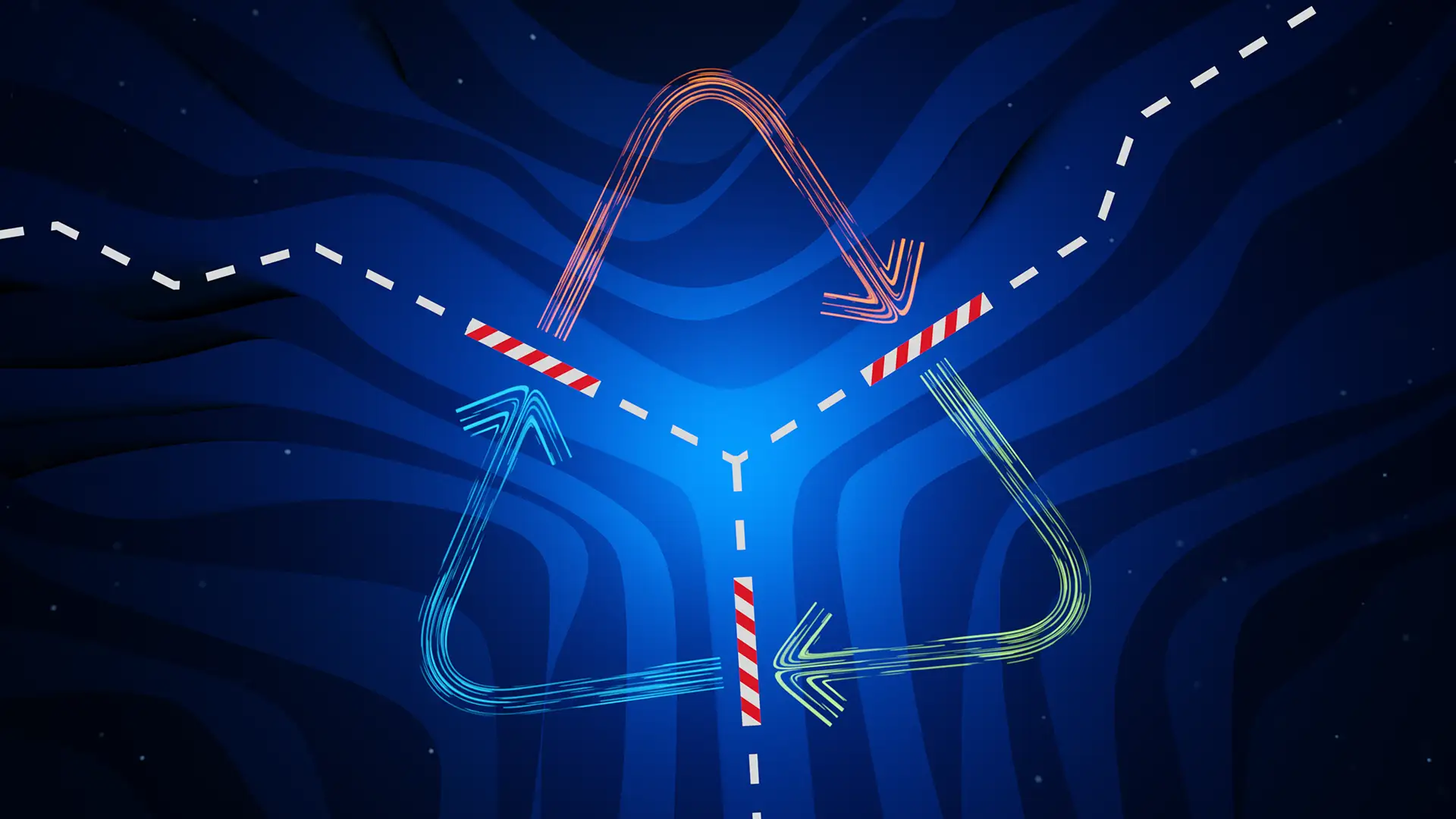

At industrial scale, although there are some opportunities in Europe to recycle or recover large-scale volumes of waste – and transform them into useful materials – waste cannot be sent easily between different EU countries. This creates a significant problem for companies: if waste is only treated locally, and its transport between Member States is effectively blocked, it undermines the business case for recycling and thus actively counters the efforts to create a circular economy on a European scale.

The EU’s Single Market matters here. It can create economies of scale across all 27 Member States – which is especially important for the circular economy to take off – while encouraging competition and ultimately benefitting consumers. Waste management facilities in neighbouring EU countries may be geographically closer, more efficient, or cheaper to reach than domestic facilities. When waste moves across borders for purposes other than landfill, it can potentially access recycling options that are unavailable or more costly in the source country. That in turn allows national recycling enterprises to operate in an EU Single Market, affording them the possibility of more scale. Ultimately, it would mean lower environmental and financial costs for waste management. Win. Win.

Refuse-Derived Fuel or when a true EU Single Market could boost circular economy and the energy transition

This can best be illustrated by an example. At Solvay, we have an energy transition programme for producing steam that, among others, replaces coal with industrial waste, known as Refuse-Derived Fuel (RDF). There are different arrangements for importing RDF across the EU: for example, while Germany offers a competitive steam price and sufficient volume of RDF, France says RDF cannot travel more than 300km, effectively blocking imports. In Bulgaria, availability of sufficient volume of RDF is an issue and regulation limits imports to max. 50%. Indeed, although the use of RDF is actively stimulated by Bulgaria, including via imports (to improve local quality), they put a limit in order to prevent waste dumping due to some abuses linked to the actual quality of some imported RDF content.

These various local situations may either raise the cost for energy recovery plants that use these waste streams or just simply make it impossible. This severely limits the scope for private sector involvement and in turn prevents countries like Spain, where the underlying RDF market is still nascent, from advancing in its energy transition away from fossil fuels.

If the EU is serious about creating circular business models that stimulate better and more recycling and help Member States in their energy transition, a functioning Single Market for waste transport has to be part of the equation.

How to get there?

A European legal framework for waste management would need to replace the current patchwork of national waste transport rules. This would not only reduce landfills in the short term, but could also advance entrepreneurship in circular economy models in the medium to long term. In time, expanded availability of RDF would ultimately contribute to the selection of clean energy options that can help the EU’s efforts to become a carbon neutral continent by 2050.

But it all starts with how we move waste. The more evidently the circular process works, the more people and companies will be motivated to invest time and effort into the circular economy.

If waste is only treated locally, and its transport between Member States is effectively blocked, it undermines the business case for recycling and thus actively counters the efforts to create a circular economy on a European scale.

There are different arrangements for importing RDF across the EU: for example, while Germany offers a competitive steam price and sufficient volume of RDF, France says RDF cannot travel more than 300km, effectively blocking imports. In Bulgaria, availability of sufficient volume of RDF is an issue and regulation limits imports to max. 50%.